Act public, stay private: best practices for private companies

Shifting sentiment among private company founders

A significant disruption is occurring in today’s capital markets, driven by a simple fact: private companies are staying private longer. During the height of the dot.com boom, a typical company may have stayed private for just over three years before tapping the public markets. Indeed, the initial public offering was the aspiration of the entrepreneur as the best possible outcome. That sentiment is no longer true. Today, it is not uncommon to spend 10+ years as a private institution, refining business models, taking on additional capital, and generating significant revenue before going through an IPO process. Stoking the flames of disruption, U.S. IPO proceeds in 2016 were $20.1 billion, a 54 percent decline from the average of the past 10 years (Figure 1), according to data compiled by Ipreo. Finally, through a combination of various factors, the number of listed companies has fallen to 3,700 in 2015, roughly half the record high of 7,322 in 1996 and more than 1,000 fewer than in 1975.

What is causing the shift in sentiment?

Founders and CEOs are making the decision to operate as a private company longer for two primary reasons. First, companies want to avoid the significant challenges associated with the public markets, whether it is the cost associated with IPOs, ongoing disclosure requirements the threat of activist investors, or the short-term performance focus that public markets seem to incentivize. Over the last 10 years, fees associated with an IPO have remained flat, at about 6.5 percent to 7.0 percent, which means companies would look to pay about $7 million for every $100 million raised. Included in those fees are costs associated with achieving initial regulatory compliance which, according to surveys compiled by the SEC, average $2.5 million. More importantly, the ongoing cost associated with remaining compliant is estimated to be $1.5 million per year. Beyond cost, regulation also forces a level of disclosure that, in the view of many entrepreneurs, compromises the competitive edge, which is inherent in privacy. Meanwhile, the number of activist investor campaigns against public companies has seen a drastic increase over the past 15 years, many of which have resulted in director-level turnover at the company. According to FactSet SharkRepellent (Figure 2), 2015 saw 15 activist campaigns against mega cap and large cap companies that were successful in attaining board seats.

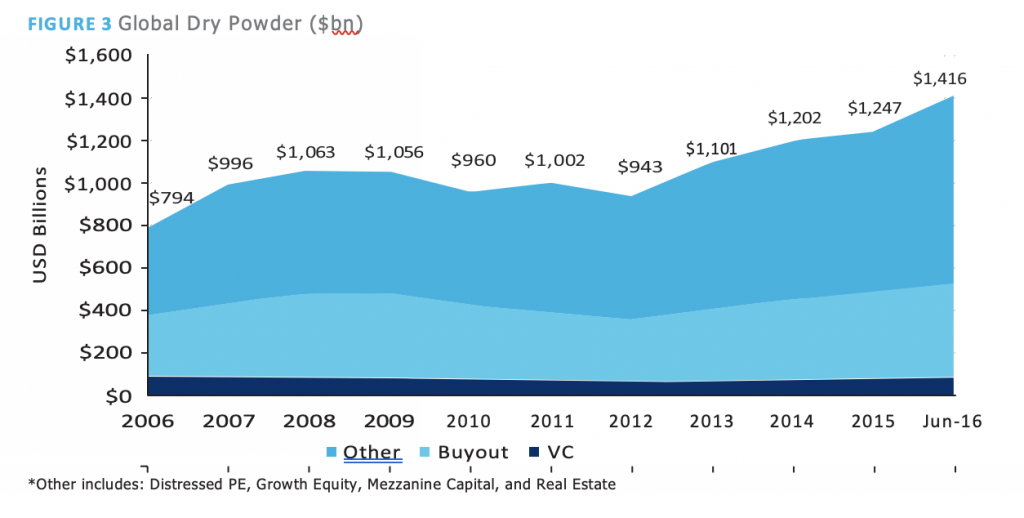

Secondly, companies are staying private longer because it has never been easier. Regulation is accommodating, and while the supply of capital is increasing, the demand for that capital is decreasing. New companies, especially tech- focused companies, have a decreasing reliance on physical assets because they are able to outsource critical capital requirements into the cloud. A significant result of this “asset-light” business model is the decreased reliance on IPOs for broad-based financing. Furthermore, although nimble, technology-enabled companies require less capital, access to capital in private markets is at an all-time high of $1.4 trillion (Figure 3). That level, which represents the amount of private capital available for investment, is a function of three dynamics: First, traditional private market investors, such as private equity firms, are raising larger funds in greater quantities as they seek to diversify investment strategies and increase assets under management (AUM); second, nontraditional private markets investors, such as institutional investors, sovereign wealth funds, and high net-worth individuals have increased allocations to private markets in pursuit of higher returns; third, given the interest rate environment, private companies may consider a greater range of financing options, which intensifies the competition to put capital to work among investors, and as a corollary, keeps more capital unspent (“dry powder”).

Gone but not forgotten

While the ability to stay private longer is clear, it does not mean that the “IPO is dead,” as many headlines have been quick to claim. After the financial crisis of 2007–2008, the global macroeconomic picture recovered, with the new issuance market leading the charge. The result of the recovery was 2014’s record issuance year, where, according to Ipreo, 807 companies raised $248.8 billion via IPO; in the United States 263 companies went public in 2014, raising $93.6 billion in proceeds. This record issuance, compounded by a slight destabilization in the macroeconomic picture globally, caused the well of capital to dry up as investors searched for yield via private investments. The year 2016 may have been a low point from an IPO perspective, however; analysts are predicting a strong recovery for the IPO market in 2017 and 2018. In an interview with CNBC, Mark Hantho, Deutsche Bank’s global head of equity capital markets, suggested that there will be 1,000 IPOs over the next two years. The initial public offering still remains a critical milestone in the life of a company, because it brings in fresh shareholders, additional capital, and, importantly, returns for those private markets investors that have been with the company since its formation. Indeed, as the recent Snap IPO highlights (in which shares sold came without any voting rights), the private to public blur is enhanced by the fact that public markets are increasingly accommodating novel structures. Lastly, while sponsor-to-sponsor deals are more common, some subset of private companies, for which strategic exits are not viable, will inevitably need to tap public markets.

An increasingly blurred distinction

For companies, however, a strong IPO market or a strong private investment market is a less relevant distinction; the critical point is that the line between public and private has blurred. From that blur emerges the key conclusion, which is that as more capital pours into the private markets, as shareholders demand more reporting, as companies take on more complicated capital structures and hire more employees, and as regulators add more regulation and heighten governance standards (which is inevitable), private markets will more and more closely approximate public markets. So then, the question facing many private companies will be, How to act public, but stay private? The answer lies in financial preparedness; effectively, the ability to more seamlessly manage critical information, track performance, and translate that data to stakeholders in a way that promotes long-term scalability (and is necessary for any company ultimately considering an IPO), and does not bring about significant back-office costs.

Act public, stay private

Regardless of the reason a company decides to remain private, this fundamental shift in the capital markets has had a significant impact on how a company needs to operate in what is now seen as the “new normal” by investors and regulators alike. As companies continue to build shareholder value to new heights while private, investors’ commitment to private capital vehicles is at an all-time high. New private capital fundraising has surpassed over $500 million in each of the past three years ending in 2015, according to Preqin, an alternative assets data and intelligence company. This heightened interest has led to a several key concerns for private companies, including but not limited to increasingly complex capital structures that come with new rounds of financing, a need for consistent investor communication, an understanding of regulatory compliance, and a need for liquidity for long-term shareholders.

While nearly all private companies are busy refining business models, gaining market share, and building a brand, it is important that they consider implementing some of the best practices below to help build a strong foundation for the long term.

Shareholder management: Shareholder communication is an important aspect for any company, public or private. A lack of communication can result in unhappy shareholders, difficulty raising additional capital, or even a regulatory violation. However, the specific requirements of a private company when it comes to communicating with its investors is a bit of a grey area and is dependent on the terms and agreements with investors. Many private companies opt to stay private because they wish to limit the amount of information they have to disclose; however, in most cases shareholders of private companies have just as much, if not more, rights than those of public companies.

Given the industry trend of companies choosing to stay private and raise new capital in the private markets, the number of shareholders requesting information and regular updates has continued to increase. In 2004, Google exceeded the number of stakeholders, 500 at the time, that allowed for a company to continue to be private and therefore not have to disclose detailed financial information. However, the Jumpstart our Business Startups Act (JOBS Act) in 2012 increased the shareholder threshold to 2,000 “holders of record,” making it easier to stay private while continuing to find new investors. As a result, many private companies have a long list of investors, including employee shareholders, yet do not have systems in place to adhere to the varied information rights afforded to investors.

This can end up with bespoke processes to handle individual or group investor requests that come at significant cost, in both time and dollars.

In order to fulfill the duties to an increasing number of investors, it is important to consider implementing an efficient investor reporting process before the investor list gets too long. This process should be incorporated for all types of sensitive information that needs to be communicated securely to investors, including regular financial reporting, updated capitalization tables following a capital raise, tax documentation, etc. While it may seem as though this much communication can be overwhelming for a small company, getting a handle on this early on can create major efficiencies down the road, and be managed by software.

Capitalization table management: As a founder or operating executive of a private company, it is critical to properly manage the company’s capitalization table, or the master ledger of ownership in the company. While it may seem like an easy exercise during the seed round of financing, cap tables can turn complex quickly when a company goes through a few more rounds of financing, issue different share classes, offer options plans to key employees, etc. If a company waits to update its cap table until its next round of financing, it may result in a prolonged fundraising process, as the company scrambles to gather relevant documentation, fix errors, and at worst, grapple with previously uncontemplated regulation.

To ensure this is done properly, it is important to engage with a lawyer around any of the aforementioned financing events; however, there are also steps that a company can take to begin managing its own cap table. While managing a cap table in a spreadsheet is one way to capture each transaction, this method can prove to be error prone the more complicated the cap table becomes. Many companies opt to use an online platform that can automate cap table management, or else enlist the help of a lawyer to assist in ensuring the accuracy of each transaction. Many of these online platforms also allow for private company executives to understand the implications of a new capital raise on their own ownership. This can help drive better decisions around how much to offer in a new round of financing and how it will impact existing shareholders during any liquidation event.

Compliance: SEC compliance is a daunting and costly proposition for both public and private companies. The challenge of compliance is compounded by the fact that many private companies do not have the legal experience or capital to make sure they are adhering to all the regulations that apply to them. Section 220 of the Delaware General Corporations Law, Section 1501 of California Corporations Code, Rule 701 of the Securities Act of 1933, and the Recognize, Assist, Include, Support, and Engage Family Caregivers Act (RAISE Act) of the recent Fixing America’s Transportation Act (FAST Act) all apply to private companies, but it is estimated that thousands of private companies are noncompliant with at least one of these regulations, according to research done by Lowenstein Sandler. In 2016, the former head of the SEC, Mary Jo White, spoke to Silicon Valley leaders about the importance of regulation for privately held companies. She stated, “From a securities law perspective, the theory behind the private markets is that sophisticated investors do not need the protections offered by the robust mandatory disclosure provisions of the 1933 Securities Act.” White followed with the statement that all market participants, public and private, look to lose if there are no regulatory guidelines in place to help standardize reporting and valuations from private companies. The complexity in solving the regulatory headache lies in the fact that it is an ongoing and evolving problem. As an executive, having a complete operational picture, whether it is an always up-to-date financial view or detailed understanding of a firm’s cap table, allows a company to stay compliant and quickly adapt to new regulation.

Employee compensation: In order to grow, private companies need to attract and retain high-performing employees, which can be a difficult proposition, given that base salaries within public companies are generally higher than those at private companies. On average, public companies pay CEOs $244,873 more than privately held company CEOs, according to data provider CapIQ, with other positions seeing similar differences in base salary pay. Private companies look to bridge this gap by offering current and prospective employees partial compensation in the form of stock options. This method aligns employees with the success of the company, as they can see net worth grow as the company continues to hit various milestones. In order to address questions on value (i.e., “Sounds great, but what could those options be worth?”), and thereby expedite hiring processes, companies can implement systems that provide prospective hires and current employees detailed scenario analytics on how much their options will be worth upon realization of various value drivers, such as growth in revenue or earnings before interest, tax, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA); or for earlier stage companies, achievement of key performance indicators (KPIs).

A second issue prevails as illiquid companies remain private longer: traditional modes of compensation come under pressure. For example, as companies remain private longer, employees have limited ability to exercise vested options and thereby access liquidity, which may be required for “life” events, such as mortgage payments or financing a child’s college education. Increasingly, companies offer employees partial liquidity programs, which allow shareholders to sell stock, allowing them to tap some of the value that they were instrumental in generating. A central repository of data allows founders to distribute and retain important documents, inform scenario analytics, and most importantly, create confidence that the cap table of a company is not being diluted in order to retain key employees.

Promoting scale: “Growing pains” are a problem that afflicts all companies, regardless of industry or size. Systems and processes that worked at one stage of a company’s life may be completely ineffective at another. The trouble is that at young, high-growth companies, the focus is on revenue generation and fundraising, rather than the implementation of systems that ultimately make scale sustainable. A company that manages all of its documents, financials, and reporting on one cloud-based solution will be able to handle scale quickly, because data is organized and highly extensible, allowing companies to deploy systems that meet the demands of the future.

Conclusion

While there has been a significant shift in the capital markets, in that private companies are opting to remain private rather than pursue an IPO, it is important to note that there is also a notable change in how private companies need to operate in this “new normal.” Facing scrutiny from limited partners, who have put record amounts of capital to work in alternative asset vehicles, and regulatory organizations, such as the SEC, many investors are requiring new levels of communication and governance from private companies that receive investment. Whether change originates from investors, regulators, or management teams themselves, one thing that is clear is that private companies need to begin “acting public” and should prepare for increasing levels of governance, regulation, and transparency. Ultimately, there will be a time when a company needs to decide the best path forward in driving growth, whether that means pursuing an IPO or raising a new round of private capital. Success for private companies will be a function of financial preparedness, which will inform smooth fundraising, optimize valuations, and streamline compliance.

Charlie Young, Executive Vice President and Managing Director, Ipreo