1BusinessWorld

1Navigator

How to raise venture capital

Among potential financing sources for new companies, venture capital (VC) occupies a unique position. Venture capitalists (VCs) are the only class of professional investors whose sole occupation is to study, finance, and support startups. They generally invest $1 million to $10 million in an early-stage venture in exchange for a significant equity stake—10 percent to 30 percent. The significance of the investment typically gives the VC firm a seat on the board of directors, which allows for direct influence on strategic decisions. VC investors are richly rewarded for backing winners, including the professional reputation that comes with success. That reputation enables them to continue raising funds and to attract “deal flow”—the next wave of talented entrepreneurs and their startups.

Although VCs invest in only a small fraction of all startups, many of the most successful startups in recent decades have relied on VC funding (e.g., Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Genentech, and Google). As a result, VCs have a unique perspective on opportunity evaluation, deal structure, new venture support, and exit. Indeed, their work at all stages of the entrepreneurial life cycle offers many lessons to company founders, even those whose ventures are not backed by VC.

Because VCs are paid, full-time investors with a strong incentive and a duty to represent the needs of the investors (known as limited partners) who contribute to the VC funds, VCs’ motivations and incentives can sometimes conflict with those of entrepreneurs and their startups’ stakeholders. Conflicts are generally outweighed— at least in successful deals—by the alignment of interest between the entrepreneur and the VC. Everyone wants the company to be successful, and everyone wants to make money. But an important part of building a successful partnership is being aware of potential conflicts and dealing with them openly and professionally.

There is certainly a subset of entrepreneurs who, in their heart of hearts, would love to get a check from VCs and never see them again (until perhaps the dinner celebrating the big sale or the Initial Public Offering [IPO]). And there’s a subset of VCs who would love nothing more than to be on the other side of that deal—to write the check and get a big payday with little or no work in between. But experienced VCs and entrepreneurs know that there is much to be gained from a true partnership. VCs as individuals and VC firms as institutions are pattern recognition machines—they have seen how various choices and strategies play out time and time again. They can’t be as close to the day-to-day operations of the business as the entrepreneur, which has its benefits and drawbacks—objectivity and distance can provide valuable perspective. Hanging over the whole relationship is the fact that, on average, VCs replace company founders about half the time. So entrepreneurs are understandably nervous about giving VCs too much power and the interactions have high stakes, requiring a healthy give-and-take as well as an open and respectful relationship.

What are venture capitalists looking for?

The venture capital deal-evaluation process is sometimes described as a three-legged stool, in which the legs are the market, the technology, and the team. There is a perpetual argument about which leg is the most important. Indeed, it can be seen as a kind of a “rock-paper-scissors” problem in which each option can be overcome by another:

- The market is the most important, because a good market will make up for a mediocre

- The team is the most important, because the market is unpredictable and a good team will find the good market

- The technology is the most important, because without a defensible, competitive advantage, it is impossible to sustainably hold on to the value created, even in an attractive market with a good team.

A robust business model with solid margins, high rates of recurring revenue, and long- lived customer relationships will add another positive dimension to the argument the entrepreneur is making for funding.

Finally, it is worth remembering that the funding decision plays out not like a snapshot but like a movie. As the VCs get to know the entrepreneur, the team, and the idea, they have the opportunity to judge how the founders develop and execute their plans (or experiments) and respond to new information and setbacks. VCs know that the early speed bumps a startup faces are generally minor compared with the issues that arise once they have more employees and invested capital on the line. But watching an early stage startup make progress, achieve important milestones, and make adjustments in the face of setbacks provides a great deal of valuable data for a VC trying to make an investment decision.

VCs are looking for passion and commitment, traits that will be required to sustain the venture across the many obstacles and hurdles it will face. But they also want to see a team with intellectual honesty, analytical rigor, and the ability to learn from experience. Most businesses—especially successful ones—don’t succeed with their original business plan. Early contact with customers and with the market generates new information and insights that must be digested and incorporated into the venture’s plan. The courtship that plays out during the search for funding is an opportunity for VCs to evaluate the team’s ability to pivot when it needs to. Moreover, good VCs can demonstrate their value by serving as useful sounding boards and can provide insights based on their own varied and extensive experiences.

Of course, throughout their relationship with a startup company, VCs are paid to be focused on one and only one thing: a financially successful exit. VCs know that even an ideal arrangement of all these variables and ingredients can nonetheless end in failure, and, conversely, a less-than-perfect set of circumstances can still yield great success. There is a lot of luck and good timing involved.

Again, this all points to the advantages of a true partnership, in contrast to a more transactional relationship, which has as its only objective the procuring of a check from VCs and the generating of high returns. The partnership model offers a greater upside for both parties.

The venture capitalist's decision-making process

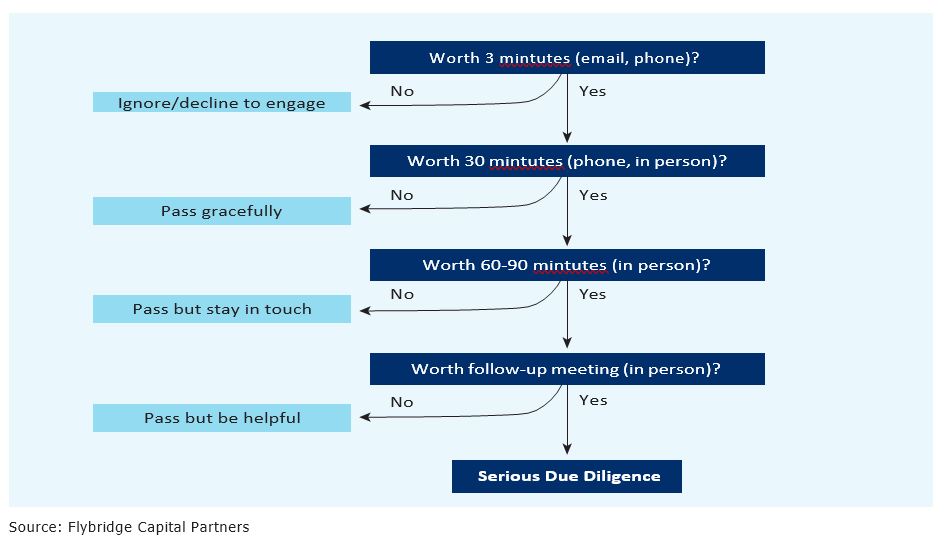

VCs evaluate deals through a complex process that serves as a funnel: The number of deals under active consideration decreases as the VC does more investigatory work, known as due diligence. (See Figure 1 for an example of the way one VC firm thinks about the decision process.) As the exhibit suggests, VCs invest more time as the number of deals they are investigating shrinks. An initial meeting or phone call will, if successful, lead to a longer, more in- depth meeting and, potentially, meetings with a broader set of the startup’s team members. The VC will call the new venture’s customers (if they exist) and try to learn about what competitors are doing. At some point, if things continue on a positive track, VCs will have their partners meet the entrepreneur and possibly the team.

The VC wants to get a look at every interesting startup, particularly those led by proven entrepreneurs. The more deals VCs see, the more likely it is that they will find a high-quality deal in which to invest. Moreover, VCs become smarter as they look at more deals, learning from the wide variety of potential investments. Note that although individual VCs do much of this work on their own, the decision-making process is collaborative. Many firms are large enough to have several professionals who invest in the same area—say, software, biotech, Internet, or cloud services. One will generally be the lead (and will serve on the portfolio company’s board if the investment is made), but investment decisions are usually made by the group as a whole. Some firms require unanimity among partners before a positive decision is made; others have a lower hurdle, such as a majority or supermajority. Often a designated devil’s advocate will try to make a case against investing to be sure the risks are fully fleshed out.

The volume of potential deals—each partner may see between 300 and 500 per year—poses a challenge. VCs struggle to sift through all the plans, people, and data to select the startups they wish to fund. Active VCs—who join the boards of the companies in which they invest— typically have the capacity to do just one or two deals a year. Passive VCs—who often invest at a later stage in a company’s life, take a smaller ownership stake, and don’t join the board—can typically invest in only three or four deals a year.

So the volume of proposals is large, and the number that gets funded is small. How can an entrepreneur improve the chances of being one of the chosen few? It’s crucial to keep in mind that the process of building a partnership with a potential VC investor begins before the first meeting even takes place. The nature of the introduction, the emails, and the material sent in hopes of gaining a meeting all establish the identity and credibility of the entrepreneur. Several steps will help.

Find a trusted source to make an introduction. The source of the introduction can send a powerful signal to the VC. Instead of making a cold call or sending an unsolicited plan in “over the transom,” the entrepreneur should get as “warm” an introduction as she can. The odds of a follow-on conversation are much higher if someone who knows the entrepreneur and is known and trusted by the VC makes an introduction. The best introductions to VCs come from people VCs have reason to trust: entrepreneurs who have made them money or the entrepreneurs in their current portfolio companies. The next tier down would include the wider pool of executives in the VC’s portfolio companies, as well as lawyers, bankers, and other service providers who work with the VC firm. Of course, the more someone has to lose by making a bad introduction, the more the VC will tend to take it seriously. And the more the VC trusts the judgment of the person making the referral—by having seen that judgment play out over time—the more time and energy the VC will invest in understanding the new venture. This means that entrepreneurs with a broad network of relevant contacts may find it easier to be introduced to VCs. Indeed, research shows that the depth and breadth of an entrepreneur’s social network can have a positive effect on the search for funding. Because new ventures are inherently risky, anything that reduces that perceived risk—such as information about the entrepreneur’s character and abilities, gleaned through a network of relationships—can help the entrepreneur secure financing.

Build a strong reputation. Entrepreneurs should work on building their reputations long before attempting to raise funding. Entrepreneurs naturally establish their reputations by behaving in a trustworthy and honorable way and by being known to others. Today, being known is accomplished by means of both face-to-face and virtual interactions. Blogging, tweeting, appearing at conferences, speaking, making an effort to become acquainted with key players in the industry, and having something to add to the conversation—all help build an entrepreneur’s reputation and network. Research has shown that the extent of an entrepreneur’s “reputational network” (i.e., the range of people who know an entrepreneur by reputation, even if not personally) can have a positive effect on the success of the venture. This reputational network is based on the entrepreneur’s relationships with market-leading firms, such as well-known technology or distribution partners, and customers.

Conduct due diligence on VCs. Entrepreneurs need to perform due diligence on their potential investors. VCs all have reputations that are based on their earlier work with companies.

Entrepreneurs must figure out which startups their prospective VCs have financed and worked with (they will usually list their portfolio companies on their website) and talk to entrepreneurs at those companies. Were the VCs available? Helpful? Did they have a wide network of relevant contacts, and did they open up that network to the entrepreneurs? Were they supportive of management and work as part of the team, or were they more likely to be critical observers? How quickly did they pull the trigger in changing out management when things were not going according to plan? These are important dimensions of the way a VC works with portfolio companies, and entrepreneurs should understand them before entering into this important partnership. Note that there is no perfect VC for every startup. It is a question of fit between the particular kinds of help the startup needs and the specific value an individual VC can add. Style and personal chemistry are important, as well in working together in a productive, trusting relationship.

An entrepreneur should consider the “sweet spots” of individual VC firms—each has its own experience and expertise. This requires an understanding of the areas in which VCs invest and the way in which markets are segmented, for example, big data analytics, medical devices, mobile advertising. It is not smart to go to a VC who has invested in a direct competitor, but it is helpful to pitch to someone who has invested in and knows the industry, and it is even better if the VC has had a successful investment in that space or an adjacent one. Many VCs also specialize by deal size and stage. But perhaps more importantly, individual venture capitalists within a firm often have their own areas of focus. An entrepreneur’s chances of success in approaching a particular VC firm may be maximized by getting on the radar of a particular VC partner at the firm.

Getting to know VCs and their reputations has never been easier. Many VCs and their firms blog and tweet, providing transparency into their areas of investment interest and how they work with startups. There are numerous specialized media properties that focus on the world of startups and VCs, from the mainstream (e.g., Fortune, Wall Street Journal, Forbes) to the niche (e.g., TechCrunch, Re/Code, StrictlyVC, Axios).

Most VCs use LinkedIn or their website bios to provide a comprehensive list of investments; speaking with entrepreneurs at those companies, both the successful and unsuccessful ones, can be invaluable. Finally, service providers who specialize in the startup world, such as attorneys, search firms, and accounting firms, have behind- the-scenes knowledge of VCs that cuts across many startups. Any and all sources of information to gain a perspective on what it will be like to partner with a particular VC individual and firm should be utilized.

Develop a good pitch. The entrepreneur also needs to hone the pitch she will present to VCs.

Once due diligence and analysis—by both VC and the entrepreneur—are completed and the VC has signaled intent to invest in a startup, the VC will bring the investment proposal to the firm’s partners for a formal vote. They will discuss the pros and cons, the risks and the upside, as well as other VC firms that might be involved (if any), investment amounts, and the specifics of the security the firm will get for its investment.

- Hit the sweet spot. Gail Goodman served as president, CEO, and chairman of the email marketing firm Constant Gail estimates that she was rejected by more than 40 VCs before securing her first round of VC money and by over 60 before securing her second. Although there was some overlap between the two rounds, this means nearly 100 VCs were wrong to turn her down—the company went public and later sold for over $1 billion. Gail’s experience would suggest that the biggest lessons are to be tenacious and work hard to find the right firm as well as the right person at the firm and, as in a general sales process, determine that they are a fit for what you are doing.

- Get the right people on the team. You need to be the right person, and have the right team, to pursue this compelling vision and bring it to life. Ideas are a dime a dozen. Having a world- class team that can uniquely execute on the ideas is All venture capitalists worry, “What happens if a ‘fast follower’ comes up with the same idea, raises more money, and recruits a better team?” The entrepreneur who has a clear, unassailable competitive advantage—an “unfair advantage”—is the most compelling entrepreneur when it comes to the pitch, and the team may very well make the difference.

- Have a compelling vision. You need a vision, an idea, an approach that gets the venture capitalist excited. LinkedIn cofounder and chairman Reid Hoffman’s idea about how the Internet might be harnessed to bring professional people together caught the imagination of several venture capitalist. The more dramatic and unrealized the vision, however, the more the experience and expertise of the entrepreneur come under scrutiny by the venture capitalist. That’s why people are perhaps the most important attribute required in order to attract VC money.

- Demonstrate momentum. As discussed, venture capitalists like to invest in movies, not still photos. In other words, they like to see how a story evolves over time so that they can extrapolate what will happen over the next few If you can show momentum in your business—across any metrics or strategic objectives—you can build momentum in the investment process. If the story gets better with time, you pique VC interest and give the impression of being a “hot” company and therefore a “hot” deal.

So, venture capitalists are looking to back entrepreneurial teams that can effectively execute the big vision and make it a reality. As Fred Wilson of Union Square puts it, “We venture capitalists love to invest in the serial entrepreneur who’s done it before, knows the playbook, and won’t make any of the rookie mistakes. And when those people come back, if they still have the fire in their belly to do it again, we’re likely to say ‘yes’ almost every single time.”

But experience cuts both ways. Entrepreneurs who know physics don’t believe they can defy gravity. Many venture capitalists prefer young founders who are incredibly brilliant and gifted even though they are inexperienced and naïve. Look at the case studies of the successful startups begun by college dropouts, such as Microsoft (Bill Gates), Dell (Michael Dell), and Facebook (Mark Zuckerberg). Fred Wilson’s observation about Facebook in the early days was that the singular focus of the young entrepreneur is very powerful. “You have this twenty-five-year-old founder, Mark Zuckerberg, who doesn’t have a wife, doesn’t have kids, doesn’t have anything in his life that’s distracting him from what he’s trying to do. And there’s nobody saying to him, ‘God damn it, take the money off the table. You should sell it now.’ Instead, he’s going for a hundred billion!”

The combination of these three forces—finding the right VC match, having a compelling vision, and assembling a uniquely strong team—is very powerful and attractive to venture capital firms.

Without question, the odds are stacked against the entrepreneur. It can seem hard to get access to a member of the VC club and convince its members that your story is a compelling one and that you have the right team to execute against it. But with good preparation and thoughtful planning, a warm introduction, and a set of well- defined experiments and milestones, you can improve your odds considerably.

Jeffrey J. Bussgang, Cofounder and General Partner, and Senior Lecturer, Harvard Business School, Flybridge Capital Partners