1BusinessWorld

1Navigator

Public relations and the age of context

Public relations has long been heralded as a cost-effective marketing tool to gain customer mindshare and industry awareness, even if some people’s murky understanding of PR was just a “trophy” article from the New York Times or Fortune Magazine—the kind of piece that executives were convinced resulted in an apparent rise in sales and growth. A connection between press and sales may have been true in an era when media outlets were as authoritative as their circulation reach was impressive. A story from the venerable Wall Street Journal columnist Walter S. Mossberg could make or break a product. But once the Internet started disrupting traditional media models about 15 years ago and then social media upped the ante five years later, the connection between PR successes and business achievements grew more opaque.

In this chapter, we will examine how PR programs are successful today and, using the technology industry as a proxy for other contemporary industries, we will examine how PR has evolved and why. We will offer some insight into how developments in the news media and media technologies have shaped PR practices, how those practices are productive and in some cases unproductive, and how those practices may offer some productive approaches to PR in most growing businesses.

Thomas R. Friedman, the New York Times columnist and author, suggests in his newest book, Thanks for Being Late, that the volume of developments in the technology field in 2007 dwarfed any other period in recent history. The advent of powerful mobile phones, information platforms like Twitter and Facebook, and infrastructural developments in creating, storing, and delivering data forever changed how we author, distribute, and share information. No other industry has felt the seismic disruption those developments created more than the news industry and therefore, by extension, public relations.

The influencer's guide to brand awareness

But, before examining that shift, it’s probably worth investigating why PR had become so critical to so many young companies. Public relations had always served the tech industry well, simply because it was hard to explain complex concepts in ads, so PR was a natural alternative marketing medium.

Out of the ashes of the dot com boom and bust, one of the consistent technology categories that had moved almost effortlessly from corporate to consumer users was computer security. From the first notable virus, dubbed Melissa, companies like Network Associates (now McAfee) and others had seized on the opportunity to protect consumers from the growing scourge that could paralyze personal computers. By 2002, Symantec’s Norton AntiVirus software was a massive seller.

But viruses were essentially pieces of digital graffiti created by attention-seekers, modern versions of “Kilroy Was Here.” Then, along came spyware.

Spyware was a very different animal. It was distributed differently, requiring users to click on something to acquire it, but it also had a much more malicious intent. Viruses were after recognition, seeking the limelight. Spyware was after your money and it wanted to be well under the radar.

A small Boulder-based company called Webroot Software had identified the problem and an opportunity. With a new product called SpySweeper, the company embarked on an aggressive PR campaign to educate consumers about the peril of spyware. Its message was simple: viruses are graffiti; spyware is criminal. And they talked to anyone who would listen. The idea was to articulate the difference and create a new security category beyond viruses and spam, the two most popular problems.

The company’s savvy CEO, a Kellogg-School- educated first-time chief executive, recognized that PR could help catalyze the category and the company and initiated a year-long effort of courting influencers through a series of product announcements and face-to-face meetings. He was knowledgeable and charming and within a year, three critical events coincided, all in the span of one month. A comprehensive cover story appeared in PC Magazine, the most influential consumer computer magazine in the world.

The New York Times editorial board called for Congressional investigations into spyware. And the United States Federal Trade Commission announced an “open-house” discussion on the commercial impact of spyware.

Within five years of launching SpySweeper, Webroot had gone from a company that fit in one conference room to a company with 500 employees in offices around the globe. A significant contributor to that growth was PR.

This is a familiar pattern: find a compelling issue, create a differentiating message, convince media to share it in a network effect, and then use that attention to disrupt market leadership. And companies like Webroot have used it very effectively.

But the most critical point is the ability to get the media to create the network effect necessary to spread the word.

The rise of social, the demise of media

It’s no coincidence that Webroot’s success occurred before Friedman’s seminal year of 2007. In today’s world of PR, Webroot’s game plan might not work. The reason has little to do with execution or strategy and more with institutional changes in the media landscape. And that comes back to 2007.

Between 2007 and 2010, both Twitter and Facebook changed irrevocably. At the South by Southwest (SXSW) Conference in 2007, Twitter experienced its first inflection point when it surged to 60,000 daily messages. By 2010, people were sending 50 million messages a day on the platform. The period was just as important to Facebook. At the beginning of 2007, Facebook had about 12 million active users. Within three years, by 2010, it had over 600 million active users.

The impact of social media on the news business—and therefore PR—cannot be overstated. Combined with the inexorable shift from analog media to digital, the result is a shrinking newsroom at most major media organizations. The trend is well documented. So is its impact on PR.

At the end of this critical 2007–2010 period, the Pew Research Center conducted an important examination of the technology media world. In the study, Pew sought to understand the kind of coverage in the tech industry by looking at every article written in one year (from June 2009 to May 2010) and then examining what those articles were about. They intended to show which firms received the most coverage. But inadvertently they determined that a group of about five companies (Apple, Google, Twitter, Facebook and Microsoft) constituted close to 40 percent of all the coverage; one out of every 2.5 articles in an entire year was about just five companies. That is a stunning finding.

There’s no reason to think that situation has changed today and if you toss in a few contemporary companies, like Amazon, Verizon, and Samsung, and that number probably gets closer to 50 percent. Call those companies the Media Oligarchs.

Two other categories then emerge, the Media Upstarts and the Media Middlers. The Upstarts are those companies that flare up quickly and gain a lot of media attention. Think Uber or Square or SnapChat. They collectively garner, by estimates, about 25 percent of the media’s attention. The Media Middlers are therefore the remaining 25 percent and represent every other company. In the case of technology companies, that is a massive group that includes large and important companies like Adobe, Oracle, SAP, Cisco, Salesforce, and on and on. It’s a point worth emphasizing: if a company is not Facebook or Apple or Google, and it’s not Uber or SnapChat, then it is competing for media attention along a very long and powerful tail of companies.

The impact of that environment on PR efforts is enormous. Any young company, unless it has the rare and mostly alchemic good fortune to become an Upstart, is going to have a very hard time solely relying on PR and the media to catalyze its company into a market position that challenges legacy leaders. There is simply an institutional bias.

Content, content everywhere

As the last decade closed, this evolution in media relations became even more tenuous for PR groups, as the macroeconomic conditions of 2008–2010 further pressured the industry. Many PR agencies and departments scrambled to develop programs that justified their fees and jobs, and many of them turned to “content distribution” as a fix. The idea was simple: if the media opportunities were shrinking, create proprietary content and distribute it through any number of emerging channels, like social media and direct media or direct mail.

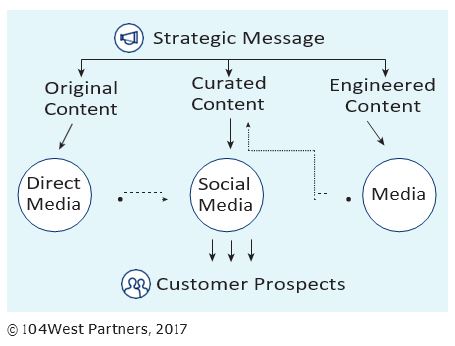

Most companies soon embarked on programs that leveraged original content, like tweets and other social posts on blogs or sites like LinkedIn, as well as content that acted like direct mail but was subtler than typical marketing material.

Many companies called that “owned” and/or “paid media.”

They also still used traditional indirect channels, or “earned media,” that reflected legacy PR tactics. Call that “engineered content” (because they have to engineer the result by persuading someone to write an article or an analyst report or offer a speaking slot). Some companies also used another category of media, call it “curated content,” taking beneficial or complementary content from third-party sources and distributing it through their own channels.

The problem for many clients and companies, however, was the content fell flat. Traditional earned media (or engineered content) had branded validation from media companies like newspapers and online blogs and TV networks, as well as built-in distribution networks. But original content struggled for both relevance and reach. And there was the thorny topic of return on the investment. Business leaders generally accepted the sort of black box of legacy PR efforts. If they couldn’t put their finger on a return, they certainly knew that the article framed on their wall was a respectable trophy.

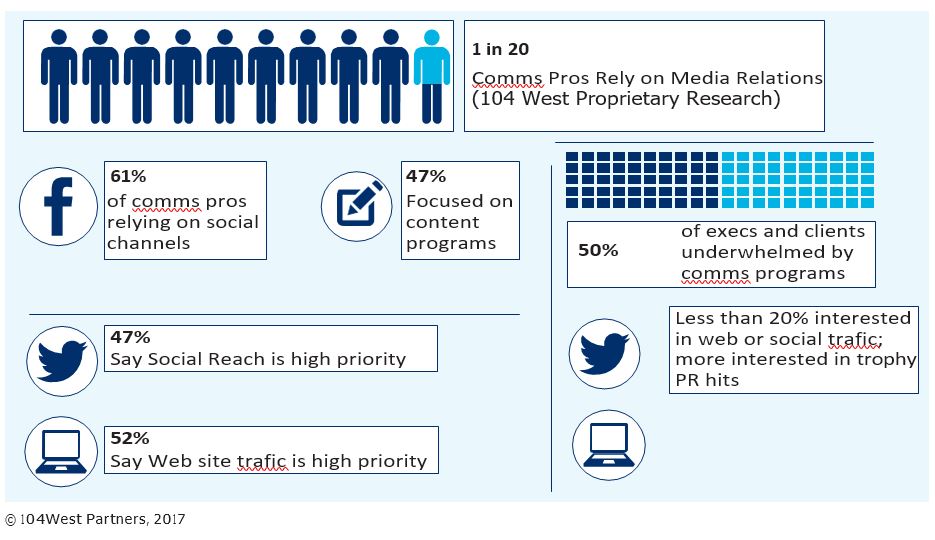

Some recent research shows a continuing disconnect between business executives and communications pros on this issue. PR and communications pros, when asked where their current program focus is, predominantly point to social media, citing among other factors the ever-increasing difficulty in attracting sustained and quality media attention. But, their bosses and clients, according to the same communications pros, still regard major articles as their goal and differ with their comms colleagues on strategy.

These execs don’t see the efficacy of the social programs their PR teams are advocating.

Presumably, the execs do want a sustained and measurable dialogue with their markets, and social content certainly provides a platform for both. But they don’t seem convinced.

It's the message, not the medium

There might be two issues worth investigating to find the solution: the medium or the message. The medium or media are certainly becoming increasingly sophisticated. Social media and direct channels have become easy to track and measure, both highly appealing attributes for senior leadership as they look to generate return on every marketing dollar, including communications.

So, if the medium with its increased sophistication and measurability is not the problem, then what about the message? One consideration is the role of context. In other words, is the content providing its audience with a message to which they can relate?

The connection between the content and the audience has taken on new importance in recent years as social media platforms became ubiquitous. Social media created a new and almost instantaneous platform for news distribution, often providing highly targeted content since people can refine their feeds according to their own preferences.

But the more significant shift is in what people do with the news when they consume it on sites like Facebook or Twitter: They share it. Facebook reaches over two thirds of U.S adults, and two thirds of U.S. adults say they get news from social sites, either from Facebook or Twitter.

The implication of this data is that the age of serendipitous discovery of news is over. Fewer and fewer people are going to news sites to find news. Instead, they are relying on social feeds to provide news for them.

That behavior evidences new willingness to consume news that is shared. If someone reads a story that a friend has shared, the credibility of that article increases. That trust extends to professional experiences as well. Content produced by professional news organizations or by companies is more engaging than content that lacks requisite context.

But context can be elusive. Many companies have turned to data as a way to have content reflect a marketplace and therefore become more engaging. It’s a simple concept: if someone sees that XX percent of people believe something and they believe that too, then they are naturally more engaged. That is highly effective, but it also requires some specialized expertise. Not all engagement is created equal. PR as a function has moved beyond the concept of publicity, something that is particularly true for business-to-business communicators who are especially keen on ROI and shy away from publicity for publicity’s sake. It’s no longer about relationships and publicity; it’s about seeing the whole field and developing programs that have greater applicability across traditional and emerging communications functions.

Even so, for years marketers and business leaders alike thought that the mere appearance of positive press would send floods of leads to their sales funnels. That is a myth. It doesn’t happen. What does happen is those articles become powerful tools that sales and marketing professionals use to engage customers and prospects directly.

The fall of the black box, the rise of measurement

If anything has changed in PR in the last decade or so, it is that PR is no longer a black box.

Instead, it is a fully realized communications function that translates messages into ideas and infuses those ideas with context to engage audiences and turns it into content.

Then that content needs to be filtered through as many channels as possible, because one of the other truths about contemporary communications is that the audience is fickle and defused. No single program element is assured an audience. But when the chorus of efforts is orchestrated right, it will resonate. And if it’s all done right, the audiences are hearing the same messages multiple times from multiple channels. When that happens, that’s truly a modern and effective communications effort.

Take the example of Rapt Media, a young company in Boulder, CO, that offers an interactive video platform. For all its popularity, video is a notorious medium for marketers and business executives because it’s very hard to gauge its marketing efficacy. People start a video and they stop a video and that action is registered. But there is really no other data, so marketers have no sense of engagement.

Rapt developed a platform that invited interactivity, thus offering behavioral data and insights. And in order to demonstrate that increased efficacy to its market, it needed to present the problem with video. In a three-part series of surveys and accompanying reports, the company asked three primary questions about greater creativity and engagement, greater funding for better performing videos, and audience reactions to these newer videos.

The resulting content was beneficial to Rapt: it said that with greater interactive technology (like Rapt’s) creative departments would develop more engaging videos that audiences would eagerly watch and react to, and therefore business leaders would fund more of them.

So, the message was on point. Next came the distribution. Of course, since PR drove the campaign, media relations was a significant component, garnering over 100 million impressions in over 100 articles over about four months. That alone would have been successful. But Rapt also pushed the campaign through various marketing and communications (marcom) channels, like SEO, direct mail, sales communications, etc. The result was impressive. Tens of thousands of website visitors were directly attributed to the campaign, representing a 65 percent increase over previous efforts, and the conversion rate of those visitors was more than 300 percent over goal.

The campaign was by far the most productive marketing and communications effort the company undertook in 2016.

Because the campaign had a strong message that translated into a compelling narrative that was infused with data to provide context and the company leveraged every distribution channel at its disposal, it created a new kind of communications that was unlike any other PR program the company had attempted in the past. The media loved it because it wasn’t some product announcement or self-serving press release. The customers loved it because it offered insight into an issue they were looking to understand better. And the company’s marketing and sales teams loved it because it offered them a string of opportunities to engage with clients and prospects and sustain that dialogue over a relatively long period.

That’s contemporary PR. The objective of most communications efforts is to maintain a productive dialogue with a company’s market over time. That is how companies change minds, create persistent brand positions, and ultimately gain market share and succeed. But the recent developments in how we consume media have changed the traditional channels. So, PR pros are looking for new ones, but they need to do that thoughtfully and with an eye toward the businesses they serve. Long gone is the era when a leading article could satisfy a client or an executive team for months. Like most of marketing and communications, business results are paramount, and so new strategies are emerging to accommodate the changing notion of what communications is and what it must be.

Patrick Ward, CEO, 104 West Partners