Successful succession planning

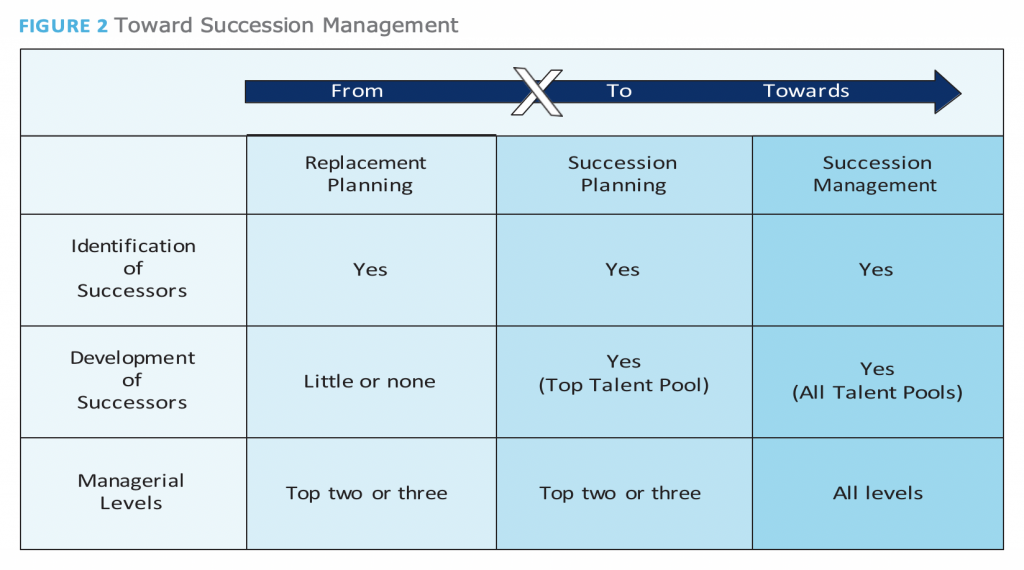

As companies grow and mature, one of the most important considerations for the future is succession management. Succession today means far more than finding that one person to step in and take over a position. Rather than simply looking for replacements, succession planning requires a broad and deep talent pipeline—that is, developing and supplying talent at the top and at other key levels of the organization.

Too often, when organizations address succession planning, they engage in a common practice known simply as “replacement planning.” The primary purpose of replacement planning is to identify immediate successors to take over a specific position in the organization should an emergency occur in which the existing executive (the “incumbent”) can no longer continue to serve. Sometimes, the replacement is referred to as a “truck candidate”; if the incumbent is “hit by a truck,” someone has been identified to take over and assume the responsibilities and requirements of the position. Replacement planning is most frequently focused on C-suite roles: CEO, chief operating officer (COO), chief financial officer (CFO), and so forth.

As a practice, replacement planning is a worthy pursuit. However, the primary fault with it is a lack of choice: the replacement is one person, and frequently this person may be the replacement for multiple positions. The replacement is often taken at face value, regardless of the changing issues, problems, and challenges confronting the organization—let alone the changes in competitive dynamics or the requirement for shifting strategies requiring skills, behaviors, and capabilities. The replacement plan is devoid of developmental considerations because it typically is not created or implemented to prepare the replacement for future needs.

Succession planning goes deeper. Its focus is not simply on preparing for an emergency replacement, but also considers multiple candidates for a given role in the organization. (The common practice is three successors identified for each role.) Successors are given comprehensive and rigorous assessments to identify their current strengths and weaknesses, the results of which are compared to anticipated requirements and capabilities of the role, and the strategic requirements of the organization. Any gaps are closed through the creation and implementation of a development plan.

In this chapter, we will look at why and how companies can move toward succession management as a best practice to prepare for their leadership talent needs in the future.

Understanding succession management

Succession management looks at talent at all levels of the organization. The practice views talent as “pools” located along a pipeline, and the pools are aggressively managed to enhance performance, build skills and capabilities, and improve leadership candidates’ overall agility to respond to rapidly changing competitive dynamics.

In contrast, succession planning is usually an annual activity. Succession plans rarely change but rather are “dusted off” from the previous year, discussed again, and then put back on the shelf. Successors are identified through nomination, which typically is a “one up” process: the incumbent identifies a potential list of successors, which is not challenged, calibrated, or validated. The list is taken on face value. Development plans may or may not be implemented.

Another way to think of succession management is that it assists the organization in evaluating its “supply” of talent against the “demand” for talent. This approach is very different from replacement planning and succession planning.

With succession management, the succession agenda is omnipresent, on an ongoing basis. Development is monitored, measured, and managed, just as the organization would do with any other resource crucial to achieving its strategic objectives. At the same time, organizations today are confronted by rapid changes: technological innovations, shifting customer expectations, new competitors, new business models, and globalization, as well as public policy issues such as environmental sustainability. Because of this evolving landscape, what makes a CEO successful today may be different in a few years. That’s why succession planning cannot involve only identifying a “replacement” CEO but also anticipating the appropriate candidate pool for the future.

Most important, succession management allows the organization is to begin identifying what I call its “seven CEOs.” This concept is just as important within maturing and advance stage companies as in a large multinational.

With seven CEOs identified—the current senior leader, plus six others at various stages in career development—organizations can meet the demands of robust succession management.

Every organization needs to consider to key questions: Who are your seven CEOs? What should you do to prepare them?

The seven CEOs

A useful analogy for understanding the concept of the seven CEOs is what air traffic controllers refer to as “a string of pearls” visible in the night sky around any major metropolitan airport. The landing flight path reveals a string of airplanes preparing to land, staged miles apart, but visible due to their landing lights. This string of pearls is a visual representation of the plan to control the flow of planes into the airport, which may be altered in response to contingencies.

Similarly, enterprises today need a “string” of seven CEOs to respond to current and future leadership talent needs. Succession management is designed to identify, assess, develop, and retain the seven CEOs within every organization. These candidates, often found deep in the leadership pipeline, are assessed to determine their strengths and weaknesses. Development plans are crafted to close any gaps, and experiences are provided to ensure that each is able to address the strategies, issues, problems, and challenges of the organization 3, 5, 7, 12, or 20 years from today. Succession management oversees this flow of talent through the pipeline to ensure the organization has the requisite talent ready and able—thus reducing the leadership risk within the organization.

One of the primary reasons for the heightened interest in succession planning and management is “Bulletin 14E” issued by the Securities and Exchange Commission in 2009. This bulletin essentially put the boards of directors of publicly traded companies on notice. Instead of the historical view that succession management was a prerogative of the C-suite, Bulletin 14E notified directors of publicly traded companies that they had a fiduciary responsibility for a company’s effort at succession management.

Subsequently, the National Association of Corporate Directors (NACD) assembled a blue- ribbon panel to focus on the board’s responsibility for the development, retention, onboarding, and succession of the enterprise’s talent. In its report, Talent Development: A Boardroom Imperative, the panel described the world in which organizations are operating today as volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous—and confounded by a rapidly emerging shrinkage of experienced senior management and executives as a result of demographic shifts. The report notes:

Having the right leadership in place to drive strategy, manage risk, and create long-term value is essential to an enterprise…the talent management challenge goes well beyond CEO succession. Do the company’s talent development efforts support its strategy and fit its risk profile? Is there a clear view of management’s bench strength—and any gaps in the pipeline—in critical areas of the business? Does the company understand what its talent needs will be in three years— or five years—in a landscape that may look very different from today’s?

Seven critical roles

The idea of identifying seven CEOs may be daunting for companies that not so long ago were lean organizations in which everyone was wearing multiple hats. Like all good practices, it begins with a process, implemented over time. Generally speaking there are seven critical roles that can be found within organizations. They are:

- Enterprise leadership, more commonly referred to as the C-suite

- Managers of businesses, who have a portfolio of businesses

- Manager of a business, a classic general managerial role

- Functional leader

- A manager of managers

- A manager

- Individual contributor

As you go down the talent pipeline, pools of potential CEO candidates expand from 3, to 10, 50, 100, 500, and/or 1,000 or more. Their readiness (their “landing,” to recall the airport “string of pearls” metaphor) may be years apart; nonetheless, they are identified, and their development can be shifted as organizational strategies and challenges alter.

Those who are “high potentials” could become part of succession management plans all the way to the enterprise level. Those who are “high performer/profession” (High Pro) are still part of the talent pipeline, but upward mobility may be more limited. Thinking in these terms allows organizations to view the leadership pipeline within an organization as repositories, or pools, of talent. Further downstream in the pipeline, the “pool” becomes broader with more potential candidates.

The value of the leadership pipeline

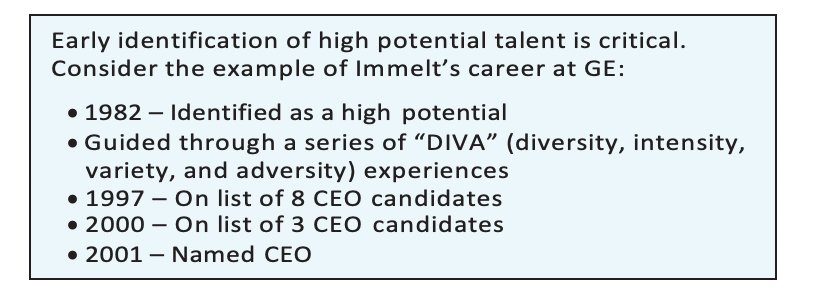

A compelling example of the value of the leadership pipeline construct to assist in identifying the seven CEOs was the 2001 succession at General Electric, when Jeffrey Immelt succeeded Jack Welch. The process was well documented and reported in the popular financial press. What is less well known is that Immelt had first been identified in 1982 as having the potential to be a GE leader at the enterprise level—though not necessarily CEO.

Immelt’s career experiences were then carefully evaluated and guided through the leadership pipeline in preparation—as were the careers of hundreds of other executives within GE. After 19 years of preparation, Immelt was one of the three primary internal candidates. He was chosen by the GE board as the best equipped to address the strategic challenges of the company (Figure 3).

As the GE example shows, succession management is an enterprise-wide practice to optimize the flow of management talent through the talent pipeline for the benefit of the organization and its individual employees. The primary focus of this practice is to ensure that executive, managerial and, most importantly, pivotal roles in the organization are filled at all times with competent internal candidates. To accomplish this, succession management includes processes to identify, develop, and deploy talent. The process also assists in the mitigation of risk for the organization and individuals. The organization wants to confirm it has the requisite talent to accomplish its strategic objectives while not placing internal candidates in harm’s way by moving them into positions that exceed their capabilities. The goal is to ensure the organization has the right people, with the right behaviors and skills, in the right place at the right time.

The process of succession management has at its core some well-developed practices, including:

- Alignment to the overall leadership and talent strategy of the organization.

- Rigorous and consistent onboarding process, assuring a seamless transition into increasingly more challenging roles for the benefit of the individual and the organization.

- Robust talent reviews that are honest, facilitated, calibrated, transparent, and based on strong performance expectations.

- Identification of the capabilities of all talent within the organization, not just a select few.

- Map of talent in which both high potential and high professional talent are identified.

- Creation and implementation of research- based development plans that can be accelerated through experiential, relational, and educational approaches, often referred to as 70/20/10 development (see below).

- Transparent process and the brokering of talent for developmental purposes that occurs across the organization.

Internal candidates and appropriate development plans

The formula for developing successful executives is quite clear: 70 percent of development comes from experience, 20 percent from feedback and people, and 10 percent from courses or training events.

Corporate directors must understand this paradigm. Experience should be the core of leadership and executive development, and those experiences should provide sufficient “development heat.” Interesting and thought- provoking courses at leading educational institutions have their use, but development plans need to be loaded with assignments—such as leading a startup or working internationally— designed to create well-tested executives. High-potential executives also should get comprehensive, multi-rater feedback each year.

Another critical component is providing coaching for emerging executives. During the next decade, the global population of 35- to 50-year-olds—the prime age of emerging executive talent—will decrease in number by 15 percent. As a result of this drop-off, companies will be forced to move talent through the leadership pipeline faster. The danger here is if unseasoned managers are put into positions of authority too quickly. If that happens, these managers may very well lack some of the competencies and skills needed in assuming the roles of senior managers and CEOs. To avoid this deficit, emerging business leaders would benefit significantly from assistance provided by a skilled executive coach with a blend of leadership expertise, human development knowledge, and strong business acumen.

Talent management plans should be monitored and measured. Here, the adage “what gets measured gets done” should ring in the ears of corporate directors. Executives devote their attention to how they are measured for merit raises, bonuses, stock awards, and recognition. Therefore, if the C-suite executives are evaluated on talent-development metrics, they are more certain to ensure talent development throughout the firm keeps flowing.

Organizations should also have in place formal assessment processes to evaluate internal candidates—with “formal” being the operative word. For those organizations that actually have one, a succession planning process typically is driven by a one-up talent review, e.g., the general manager for Brazil provides the head of Latin America with a short list of succession candidates. Typically, this list is passed upward and onward. This notoriously subjective approach is rife with documented problems, such as the “halo effect” (one can do no wrong) and personal biases toward a given person. Rather, objectivity and transparency should drive succession plans within a framework of possible strategic scenarios. These criteria can be met through a formal assessment approach.

Many companies use a performance/potential matrix, which plots where an executive sees his or her direct reports. The vertical axis is sustained performance, which takes into account a three- to five-year period, and not just the last year’s results. High performance means superior—the best performance people have seen. Middle performance indicates someone is meeting the expectations of the role. Lower performance indicates that there are conditions interfering with a person’s ability to meet the requirements.

On the horizontal axis is learning agility, which Korn Ferry views as the foremost indicator of leadership success. Learning agility is the ability and willingness to apply past experiences and lessons learned to unfamiliar or changing situations. At the intersection of the two axes— superior sustained performance and high learning agility—is high-potential talent.

A talent review using the performance/potential matrix is an invaluable exercise. Organizations also should include a 360-degree feedback process. In this approach, an immediate boss, peers, and direct reports proffer their perspectives on the current skills of the executive in question. This not only provides executives with valuable feedback, it also can measure in great detail the degree of “fit” with future requirements of the organization.

Succession planning for the future

As this discussion shows, succession today means far more than finding one person to step in and take over a particular position, especially at the top of the organization. What’s needed is a succession management approach that deepens the talent pipeline.

At a time when boards of directors have a clear fiduciary responsibility for succession, a robust process is needed to identify, evaluate, and develop a broad slate of candidates. Often found deep within the organization, these candidates are assessed to determine their strengths and weaknesses, and provided with development plans for the short and long term. By identifying their “seven CEOs,” organizations ensure they have the requisite talent ready and able to step into top roles, which reduces leadership risk.

At every stage of the process, assessment and development are key components. Strengths and weaknesses of individual candidates are identified. Based on these insights, and with an understanding of the company’s evolving leadership needs, development plans are crafted to close gaps and provide experiences to prepare for future positions. With a “seven CEOs” approach, both growth- and late-stage companies can ensure they have the talent pipeline in place to support their future success.

Reference

- Charan, Ram, Drotter, Steve, and Noel, Jim, The Leadership Pipeline: How to Build the Leadership Powered Company (2nd Edition), 2011, San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

James Peters, Senior Client Partner, Global Head of Succession Management, Korn Ferry Hay Group